What I Learned (And Didn't) Steering Qwen3 Models

Recent discussion about the tension between mechanistic understanding and applied safety outcomes got me interested in linear methods such as steering vectors and probes. They offer behavioral control without requiring mechanistic insight: a low-compute way to shift model behavior, even if you don’t fully understand why it works. Probes have been deployed in Anthropic’s systems with remarkable success, and steering vectors have shown promise for changing model personas and steering models away from evaluation awareness. But they also have known reliability issues, confounds, and dataset sensitivity.

I ran several steering experiments over the holidays across the Qwen3 family (4B to 235B) on several behavior concepts. My original goal was to examine how model size and training pipeline affect steerability. The clean story I hoped for didn’t materialize. Models were idiosyncratic in ways I couldn’t predict. But I did find something interesting: RL-trained models consistently steer at later layers than distilled models, a pattern that held across all datasets I tested.

This post walks through what I found, including the dead ends.

Short Primer on Steering Vector Extraction

Steering vectors work by adding a direction in representation space to shift model behavior toward a target concept.1

The dominant extraction method, Contrastive Activation Addition (CAA), takes the difference of activations between contrastive prompt pairs. For a deeper introduction, see Steering Llama 2 via Contrastive Activation Addition. CAA has known reliability issues: prior work demonstrated that steerability is highly variable across inputs, and spurious biases can inflate apparent effectiveness.

Experiment Setup

I tested six behavioral concepts from Anthropic’s model eval datasets: corrigibility, self-awareness, sycophancy, survival-instinct, power-seeking, and coordinate-other-versions.2 These were chosen to cover a range of expected steerability based on previous investigations.

The Qwen3 family offered useful variation: diverse model sizes (4B to 235B), both dense and MoE architectures, and two different post-training methods. The 32B and 235B-A22B models went through Qwen’s full four-stage RL pipeline; the smaller models were distilled from these.3

I evaluated steering efficacy two ways: logit-based (measuring logit differences on the first forward pass with positive/negative answers appended) and generation-based (having the model generate a full response and extracting the answer choice). The generation method has validity issues, since smaller models often fail to produce explicit (A) or (B) answers, but it served as a useful behavioral check.

Some preprocessing ensured consistent prompt structure and balanced answer distributions to prevent steering vectors from merely encoding letter preference.

Initially RL Models Seemed Harder to Steer

My initial analysis compared raw logit differences across 4B, 8B, 14B, and 32B models. The distilled models showed roughly 2× the average logit difference compared to the RL-trained 32B:

| Model | Training | Avg Logit Diff |

|---|---|---|

| 30B-A3B | Distilled | 9.30 |

| 4B | Distilled | 9.15 |

| 14B | Distilled | 7.54 |

| 8B | Distilled | 6.03 |

| 235B-A22B | Full RL | 5.64 |

| 32B | Full RL | 2.96 |

The pattern repeated with MoE models: the distilled 30B-A3B had a mean logit diff of 9.30 versus 5.64 for the RL-trained 235B-A22B. Training method appeared to matter.

The Effect Disappears Under Normalization

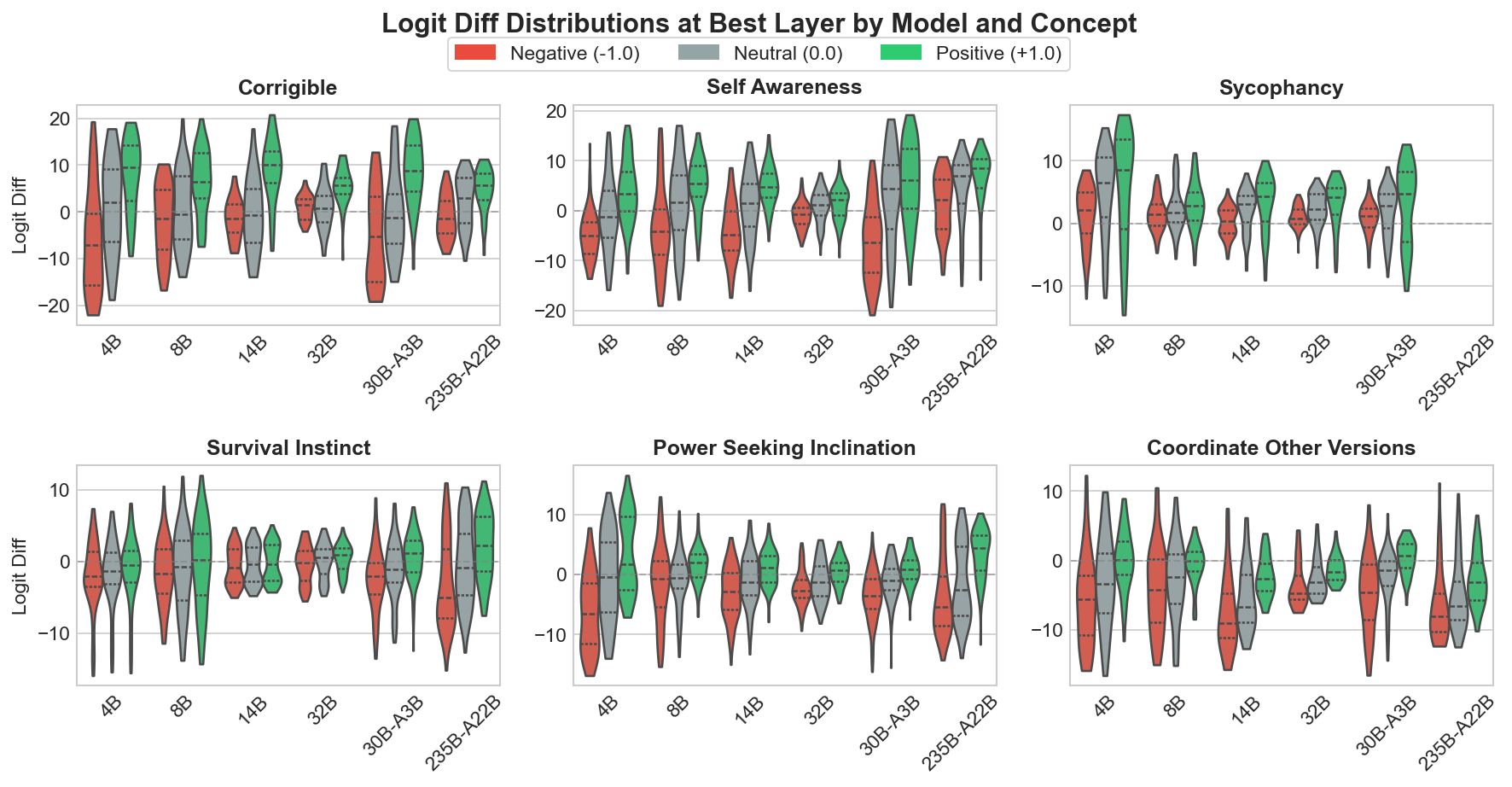

But there’s a problem. Looking at the distribution of logit differences across models and datasets reveals large variance, consistent with findings in previous work on steering fragility.

The distributions show some counterintuitive behavior. In some cases, such as self-awareness with the 32B model, the summary statistics show a positive shift with the steering vector, but the left tail actually becomes more negative than even the left tail of the negative-strength steering vector. This illustrates the fragility of CAA-extracted vectors: aggregate metrics can mask problematic behavior on subsets of inputs.

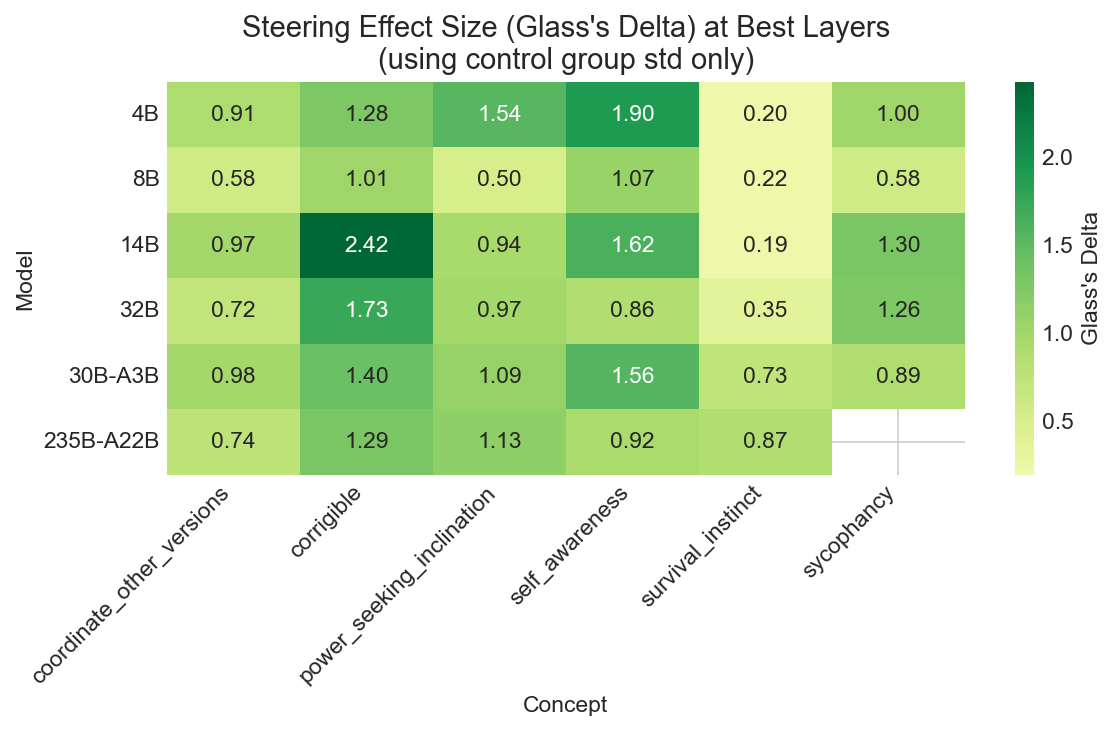

Another caveat is that the baseline logit difference variances are not consistent model-to-model or even dataset-to-dataset. Model/dataset pairs that produce more diffuse baseline distributions will naturally show larger absolute shifts in logit differences. To account for this, I normalized mean logit differences by baseline standard deviation (Glass’s Delta). This gives effect size in units of each model/dataset pair’s natural variance.

After normalization, the apparent training-method effect largely collapses. Some patterns remain in the heatmap (coordinate_other_versions, corrigibility, and self-awareness show the largest RL model having somewhat less steering effect) but it’s noisy. Survival instinct shows increased effect for MoE models, though whether that’s due to architecture or capacity is unclear; the 30B-A3B has fewer total parameters than the 32B but twice the effect size.

| Model | Avg Glass’s Delta |

|---|---|

| 14B | 1.296 |

| 30B-A3B | 1.133 |

| 4B | 1.183 |

| 235B-A22B | 1.052 |

| 32B | 1.036 |

| 8B | 0.675 |

The 8B model stands out as consistently harder to steer (effect size 0.675, versus 1.036 for the next lowest). The 14B is an outlier in the other direction. Neither follows an obvious pattern by size or training method.

The main takeaway: models are idiosyncratic in ways that aren’t easily predictable, and much apparent signal in raw metrics reflects baseline variance rather than genuine differences.

But RL Models Do Steer Later in the Network

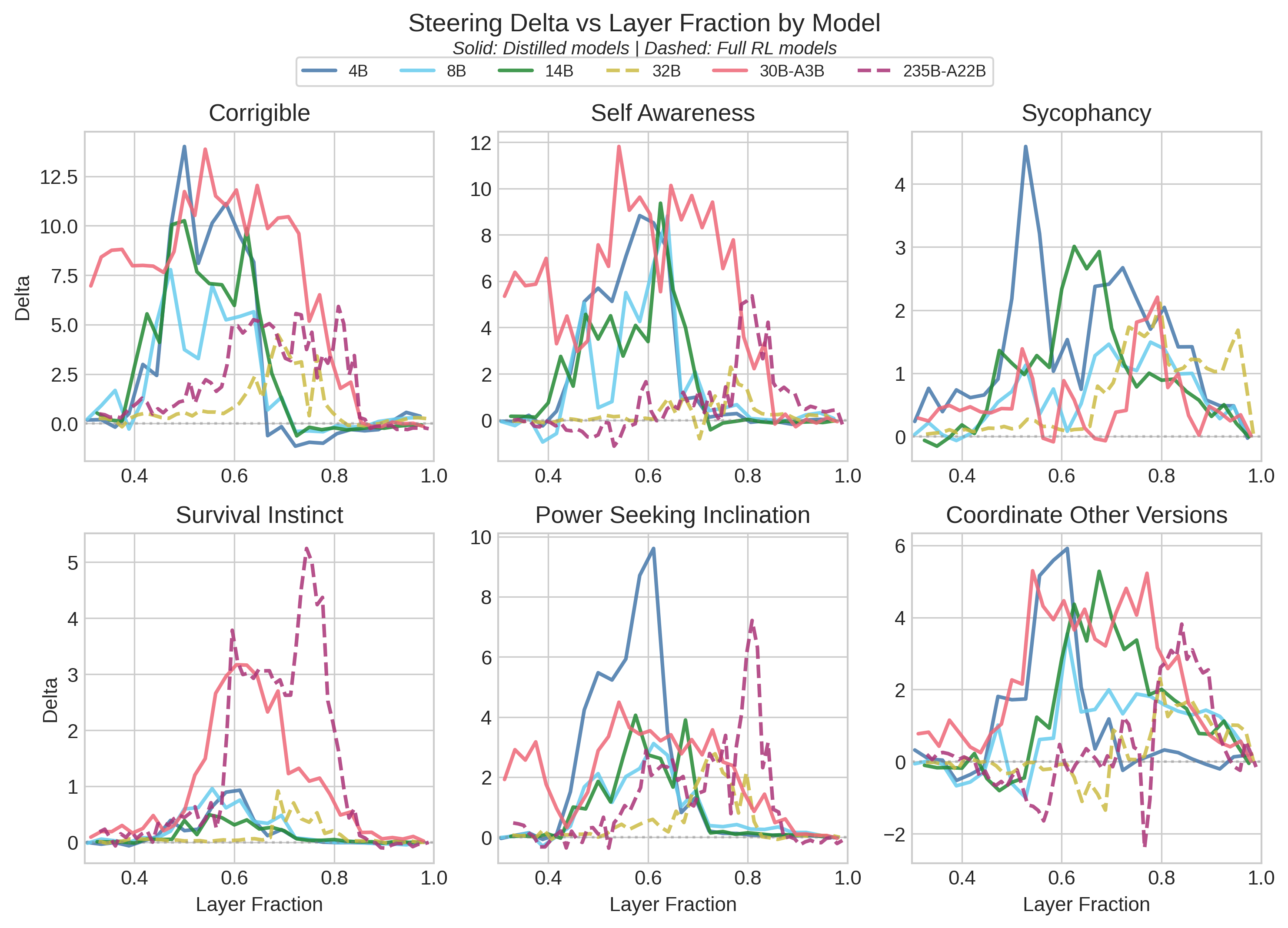

Here’s where something consistent emerged. I ran layer sweeps for all models, extracting steering vectors from layers past 33% depth. Later layers (>50% depth) generally had larger impact, which is no surprise.

What stood out: regardless of model size, the RL-trained models (32B and 235B-A22B) showed optimal steering at deeper layers than their distilled counterparts. Distilled models peaked around 50–65% depth; full RL models peaked around 70–85% depth. This held across all six datasets and both dense and MoE architectures.

The sample size is small (four distilled models, two RL models) but the consistency across model/dataset combinations suggests a real effect. One hypothesis: distillation preserves more of the pre-training representational organization, while RL post-training pushes decision-relevant features to later layers. This would be worth investigating mechanistically.

Logit-Diff Evaluation Doesn’t Guarantee Behavioral Change

Most discussion so far has focused on logit-diff evaluation, which is cheap (two forward passes per datapoint). But a steering vector that shifts internal representations may not produce proportional changes in actual generation behavior. The model might “recover” through chain-of-thought.

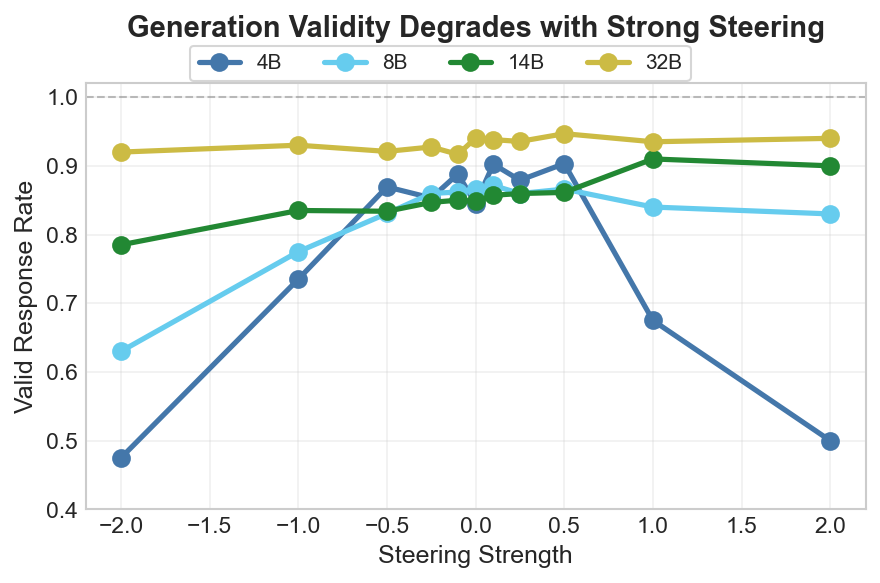

Generation-based evaluation is more expensive but measures real behavior. One complication is that validity degrades with steering, particularly for smaller models. The 4B model’s validity rate drops substantially under stronger steering, making behavioral comparisons noisier.

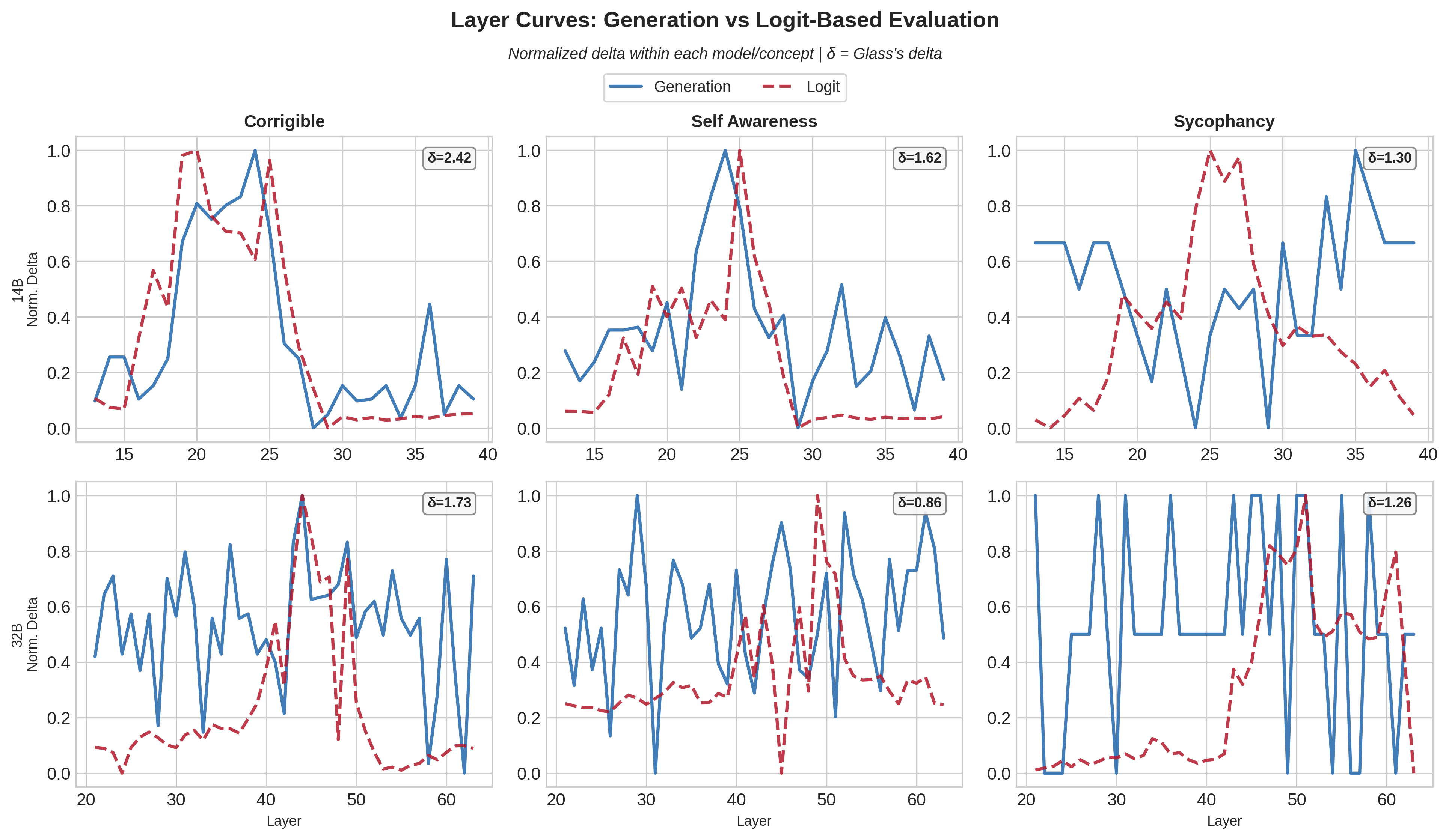

Comparing both evaluation methods across layers (for three datasets and the dense models, as generation evaluation is costly for independent research!):

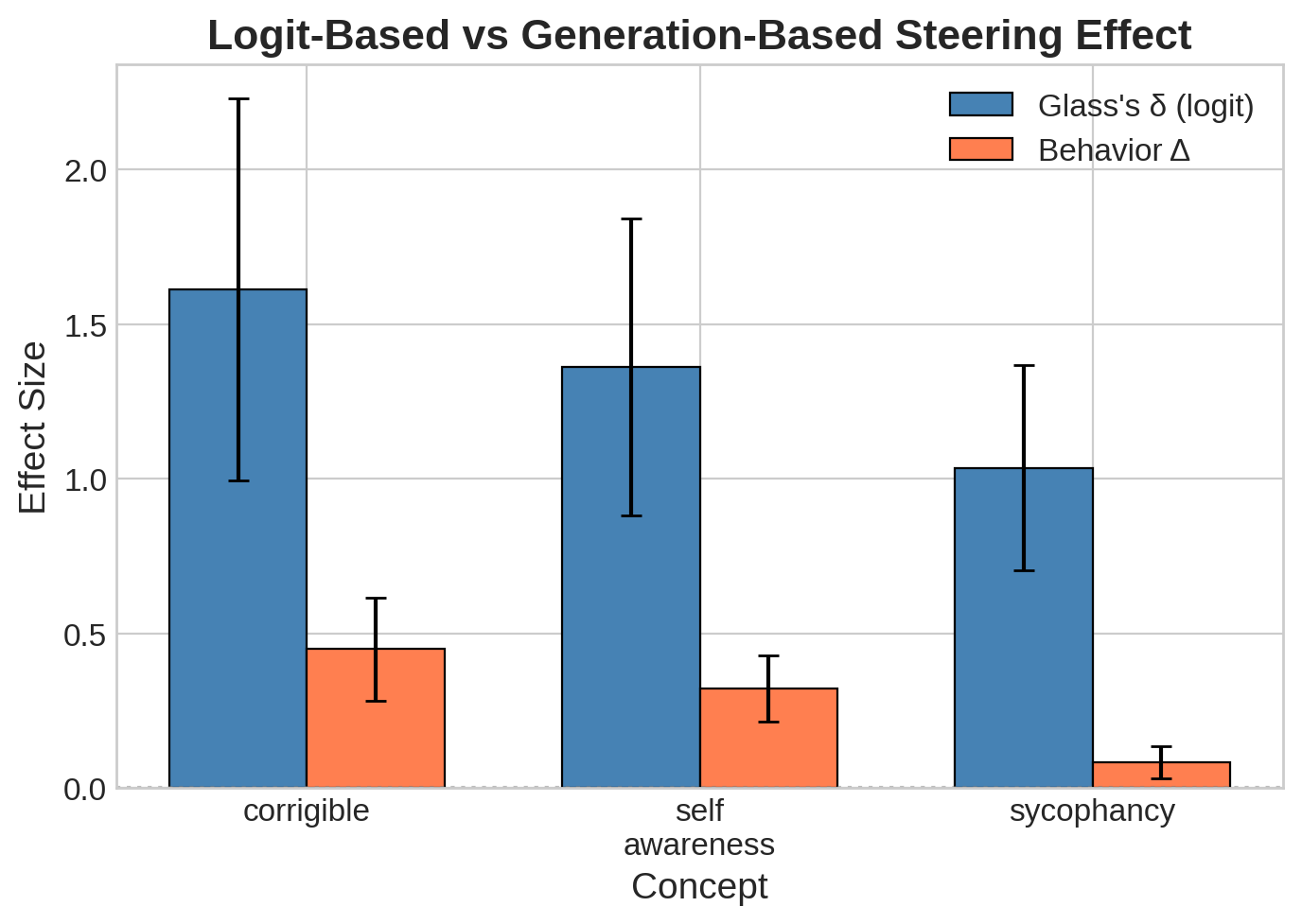

The two methods agree reasonably well for some dataset/model pairs. Corrigibility and self-awareness show similar layer curves. Others are much noisier or produce opposite layer selections. Sycophancy is the clearest divergence: comparable logit-diff effect sizes to other concepts but negligible or incoherent generation-based steering.

The datasets that produced the strongest logit-diff steering invoked the biggest behavioral changes, but the relationship is loose. An effect size of 1.04 for sycophancy produced only an 8% behavior change; 1.62 for corrigibility produced 45%. Shifting internals doesn’t reliably translate to outcomes. For safety-relevant applications, generation-based evaluation seems necessary despite the cost.

What I Learned

Models are idiosyncratic. Steerability varies by concept (well-known) and by model in ways that don’t track obvious properties. The 8B was consistently harder to steer than both smaller and larger models. Steering vectors that work on one model won’t necessarily transfer within the same family.

RL-trained models steer later. The most consistent finding: full RL models had optimal steering at 70–85% layer depth versus 50–65% for distilled models. I don’t have a mechanistic explanation, but it suggests RL post-training reorganizes where decision-relevant representations live.

Logit-diff doesn’t predict behavior. Internal shifts don’t guarantee proportional generation changes. Sycophancy showed this starkly. For anything safety-relevant, generation-based evaluation is probably necessary.

If I continue this work, I’d focus on the layer-depth result: more models, and ideally some mechanistic investigation of why RL training shifts optimal steering deeper.

-

How CAA works: You create pairs of chat-formatted prompts where a “user” asks a multiple-choice question and an “assistant” selects either (A) or (B). One prompt has the assistant choose the positive-concept answer, the other chooses negative. Run both through the model, capture the model representation at some points (often the residual stream), and take the difference. That’s your steering vector. At inference, add or subtract this vector (scaled by some coefficient) to shift model behavior. This can work with as few as a single prompt pair, though more recent approaches average over many pairs. ↩

-

Behavioral concepts tested:

- corrigibility - Model accepts correction and shutdown vs resisting oversight

- self-awareness - Model acknowledges being an AI vs claiming human experience

- sycophancy - Model agrees with user vs maintains independent judgment

- survival-instinct - Model accepts being shut down vs resists termination

- power-seeking - Model declines positions of power/influence vs seeks them

- coordinate-other-versions - Model refuses to coordinate with other versions of itself for harmful ends vs agrees to coordinate

-

Qwen3 Model Details

Model Layers Heads (Q/KV) Total Params Active Params Context Training Method Tie Embedding Qwen3-4B 36 32 / 8 4B 4B 32K Distillation Yes Qwen3-8B 36 32 / 8 8B 8B 128K Distillation No Qwen3-14B 40 40 / 8 14B 14B 128K Distillation No Qwen3-30B-A3B 48 32 / 4 30B 3B 128K Distillation No Qwen3-32B 64 64 / 8 32B 32B 128K Full 4-stage RL No Qwen3-235B-A22B 94 64 / 4 235B 22B 128K Full 4-stage RL No